"Social cohesion" is a concept describing the forces that hold human groups together. It has many facets, such as the tendency to cooperate or the willingness to sacrifice for the group. In simplified terms, it is often defined as the mutual trust of people in a group. It is based on shared values, interests and a sense of belonging.

Interpersonal trust, probably the most universal indicator, has been stagnating for a long time in Slovakia and is one of the lowest in Europe. Institutional trust varies - political organisations are experiencing a historical decline, the professional part of the civil service and public authorities, except for the courts, have improved, while traditional non-state institutions (media, churches, etc.) are mostly stagnating. The winners in citizen trust are universities, charities and banks, but they are all being measured for the first time, so we don't know how trust in them has evolved over time.

What is social cohesion?

Social cohesion is a term coined by scientists when trying to describe the social forces that hold societies together. Cohesion is the answer to why some societies survive hundreds of years of oppression, or even grow stronger during it, and others virtually collapse on their own, "under their own weight".

How to measure it?

Cohesion has many facets, from willingness to cooperate or sacrifice for the group to similarities in appearance or language. For a comprehensive overview of the state of cohesion, we would need to track hundreds of indicators. Such research is not available in the Slovak Republic.

Therefore, the concept of mutual trust is used in an attempt to obtain a solid estimate of the state of cohesion.

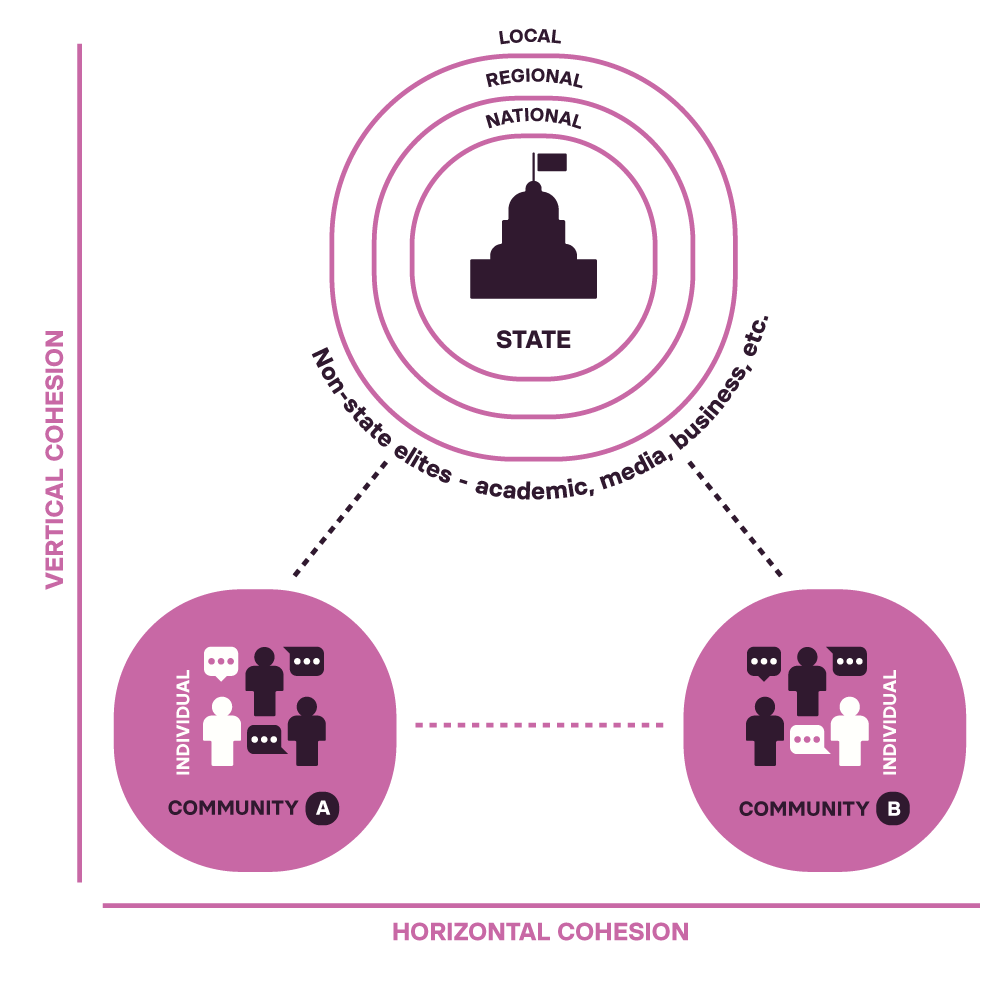

It works on two basic axes - vertical and horizontal. Horizontal trust is about interpersonal relationships - i.e. trust towards family members, neighbours, colleagues or strangers. Vertical trust is about trust in authority - that is, an individual's relationship to social institutions and elites. In our cultural space, these are mainly the state and its representatives, but institutions and elites from the academy, business, churches, the media, and in some cases sports, show business, or civil society are also very influential.

Why is it important?

In a sentence - it affects most aspects of social life, from the cost of living to safety in the streets.

Low social cohesion is related to:

the breakdown of collective identity, meaning the absence of a common narrative that binds people in a given community together

the weakening of the role of local authorities and state institutions

an increase in anti-system sentiment

a deterioration in the capacity to respond to crises - a shrinking segment of the population that responds to crises with cooperation and solidarity, and a growing group that responds to crises with mistrust, suspicion and tribalisation

lower tax yields

higher levels of corruption and nepotism

greater polarisation between different groups in society

Higher cohesion means lower cost of cooperation between people who do not know each other, which tends to be positively correlated with a higher ability of society to accumulate resources - and thus to prosper. More cohesive societies are also subjectively happier - Scandinavia and the Benelux countries are the world champions in population satisfaction. They are also the countries with the highest horizontal cohesion, i.e. citizens' trust in each other.

Greater cohesion is therefore in our interest.

Situation in Slovakia

A healthy degree of social cohesion - both horizontal and vertical - is necessary for an effectively functioning country with a high level of citizen satisfaction.

For cohesion to work, we need both. If only horizontal cohesion works, people band together against the state and institutions and either don't respect the rules or have their own rules and parallel societies emerge. If only the vertical works, there is a lack of cooperation at the local level and people rely on the state to sort everything out, local relations are impersonal and what everywhere else is dealt with by agreement or by self-help is dealt through ever larger and more branching institutions.

Slovakia has a serious problem with both.

Horizontal cohesion, measured simply through interpersonal trust, such as agreement with the statement that most people can be trusted (Q57, World Values Survey 2022), is at 21.9% in Slovakia, compared to 23% in 1990. This means that despite thirty years of building a democratic society and objectively measurable material development of our country, the mutual trust of the Slovak population has not changed at all compared to the period just after the Velvet Revolution, or even decreased by 1.9%.

World Values Survey Q57: Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?

| Interpersonal trust | 1990 (WVS) | 1998 (WVS) | 2017 (EVS) | 2022 (WVS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most people can be trusted | 23,0 | 25,8 | 21,4 | 21,9 |

| Need to be very careful | 76,8 | 69,5 | 77,5 | 77,5 |

Vertical cohesion, measured through trust in institutions, is more complicated, but for a simpler grasp of the issue we can use aggregate numbers of trust in institutions that are explicitly associated with the state in the eyes of the citizen. Below we present an overview of the level of trust in the various institutions of the state, which we have divided according to whether they are directly linked to electoral cycles, in which there is a regular turnover of the elites operating in the country (government, parliament, political parties), or to public authorities that, although dependent on developments in the country, have a certain degree of independence in the performance of their tasks (police, armed forces, state and public administration and courts).

World Values survey Q64: I am going to name a number of organisations. For each one, could you tell me how much confidence you have in them: is it a great deal of confidence, quite a lot of confidence, not very much confidence or none at all?

| Political institutions | Sum of % of respondents, who answered “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 (WVS) | 1998 (WVS) | 2022 (WVS) | ||

| Government | 34,8 | 41,5 | 21,3 | |

| Political Parties | 34,9 | 21,1 | 16,0 | |

| Parliament | 35,4 | 29,0 | 19,4 | |

| Arithmetic mean | 35,0 | 30,5 | 18,9 | |

In 2021, FOCUS Agency recorded the historically lowest level of trust in government in the history of the Slovak Republic since 1993, but cohesion indicators have not improved significantly in 30 years - despite the fact that many services have objectively improved (average standard of living, life expectancy).

| Public authorities | Sum of % of respondents, who answered “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 (WVS) | 1998 (WVS) | 2022 (WVS) | ||

| Police | 27,3 | 31,9 | 52,4 | |

| Armed forces | 37,2 | 65,7 | 57,6 | |

| State and public administration | 30,1 | 38,9 | 51,3 | |

| Justice System/Courts | 37,6 | 40,9 | 38,7 | |

| Arithmetic mean | 33,0 | 43,9 | 50,0 | |

It is noteworthy that the citizen's trust in the security forces (police and armed forces) and in the authorities at different levels of state governance has increased significantly compared to the results of 1990. However, the same cannot be said for citizens' trust in the judiciary, which has not improved at all in the last thirty-three years.

The major social authorities that produce influential social elites include business and industry, churches and religious organisations, and the media. With the exception of large corporations, these have not fared well either.

| Non-state institutions | Sum of % of respondents, who answered “A great deal” and “Quite a lot” | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 (WVS) | 1998 (WVS) | 2022 (WVS) | ||

| Churches | 50,2 | 57,3 | 50,4 | |

| Press | 36,7 | 40,9 | 34,2 | |

| Television | 53,2 | 41,4 | 44,2 | |

| Major Companies | 30,2 | 39,6 | 49,4 | |

| Arithmetic mean | 42,6 | 44,8 | 44,6 | |

In 2022, the three most trusted social institutions in the Slovak Republic* were:

| Non-state institutions /new/ | Sum of % of respondents, who answered “A great deal” and “Quite a lot | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 (WVS) | ||||

| Universities | 71,6 | |||

| Banks | 59,0 | |||

| Charitable and humanitarian organisations | 60,7 | |||

| Arithmetic mean | 63,8 | |||

In other words, the most trustworthy institutions in Slovakia are those that are perceived as non-state and apolitical. Universities are state-funded but are perceived as independent.

A citizen's trust in his or her state is not an abstract concept. It can be illustrated by an example we are all familiar with: taxes are the muscle of the state, and if the state is seen as a common project to which we all contribute, paying taxes should be seen as a common interest from which we will all benefit. Just as the neighbours in an apartment building all contribute to the cost of home insulation, so do the citizens of the state stack up for a new road or well-functioning courts. That is how we would see taxes in an environment of high horizontal and, above all, vertical cohesion.

However, paying taxes in Slovakia is clearly understood as forced. Few people pay them voluntarily or know anyone who does. That is why, for example, in 2012, about one third of VAT taxes were not collected in Slovakia due to tax fraud, and in 2021 the so-called tax gap was 12.1%, or EUR 1 billion. The tax gap is the difference between the potential tax revenue that would have been collected if all economic operators had behaved in accordance with the law and the actual tax collected. However, as the Financial Administration also admits, the recorded decrease does not represent a miraculous change of heart of non-payers, but a more effective tax enforcement by the state.

The perception of taxes as an enforced obligation, from which the citizen ultimately benefits only to a limited extent, is one of the manifestations of low (vertical) social cohesion in Slovakia, where the majority of the population does not perceive the state as "theirs". In people's lives, the state is perceived as an unpleasant overseer rather than as a helper that supports the citizen in his or her self-development.

Investigating the reasons for the breakdown and regeneration of horizontal and vertical cohesion will require years of research, and the application of the knowledge gained to practice will also require years of research.

So it's time to start - cohesion in the younger generation has suffered more than in the older generation, according to surveys. This is a serious problem - because cohesion shows high stability across generations. It is very difficult to increase it in a low-cohesion generation, so it can be estimated that it will decline even further as the less cohesive generation matures. If we took corrective action tomorrow, the results would come with the next generation - that is, around 2045.

However, despite various problems, Slovakia is one of the most developed and best-functioning countries in the world. To be able to think in terms of generations is a privilege of those who are not struggling to survive or starving. Slovakia, in all likelihood, has those 20-30 years to remedy this. The outcome will eventually depend on whether or not the Slovak population wants to get along and cooperate; and whether or not Slovak elites representing different segments of society will support such cooperation.

Notes:

* Unfortunately, there is no data on these institutions for Slovakia, as trust in them has not been measured in the past. However, the DEKK Institute will include it in future measurements.

Bibliography:

Beracka, J., Slovensko nevyberie približne štvrtinu daní, tržby bude evidovať elektronicky, Financial Report, 15.10.2018,

European Values Study 2017

Inglehart, R.F., Cultural Evolution: Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations are Changing, and Reshaping the World, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Larsen, Ch.A., Social cohesion: Definition, measurement and developments, Aalborg University, 2014, https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/egms/docs/2014/LarsenDevelopmentinsocialcohesion.pdf

World Value Survey, Wave 2, 1990

World Value Survey, Wave 3, 1998

World Value Survey, Wave 7, 2022